I’m finding this article difficult to write. In part, because I think Resource Curse is a bullshit narrative to distract from crap policy – but also, because it is a little more nuanced than that.

Resource Curse is a hazard associated with economic overreliance. If the foundations of a system is built on one industry: when that industry fails, the whole system fails. And you may be surprised, that this is seen in more than just natural resources:

For example, the United Kingdom is a highly diversified economy – however, from the 1970s to the 2000s, the UK grew into a heavily skewed service sector economy. Financial and Insurance Services accounted for 8.8% of Gross Value Added in 2008. It was the engine of the British Economy, accounting for about 20% of export revenue.

Then, the global financial crisis hit. By 2009, the Gross Value Added had reduced by 1.4% or 22 billion pounds. I was in school, I remember my science teacher telling our class how our life prospects had become – futures died.

It took eight years for the trigger sector to recover. The UK Economy still feels the economic pain today – from trying to stay afloat – and that was just 8.8% of the economy.

So suppose instead your economy is built on mineral exports: in Madagascar, Nickel accounts for 18.1% of Exports; in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, cobalt and copper exports account for 80% of government revenue; in Chile, copper accounts for half of export revenue; in Peru, copper, gold and zinc account for 60% of export revenue.

The commoditization of resources makes these industries vulnerable, and therefore can compromise economies. It becomes a question of how can a nation control the market?

The DRC is interesting in this case, there is a huge contradiction. DRC do not include the proceeds of mining for their Gross Domestic Product – however, due to their monopoly over global Cobalt production, they were able to enforce a seven month export ban – to artificially raise value.

The DRC has the power to dictate global price for Cobalt, but lacks the policy to capture that value domestically – but why?

This question gets to the roots of resource curse: corruption, conflict, leakage and linkage.

Corruption – is it easy to see a shit deal, if you’re winning? If you feel looked after, will you read the fine print? If accountability isn’t there, what’t the risk? If I don’t agree, someone else will – it’s not a game of goodies and baddies.

Conflict – the mining industry is sensitive, information is controlled: because the means of production of resources is leverage. Whether we discuss M23 controlling DRCs mines, the Taliban controlling Afghanistan’s lithium, or private military contractors in Papua New Guinea – the risk of conflict is a barrier to transparency.

Leakage – the tight control of information allows mining operators to write the rules: for example, they can export ore at low value, then process and realise the value more tax-favourable nations. The developing state still gets their tax and export duties, being short changed by their own rules.

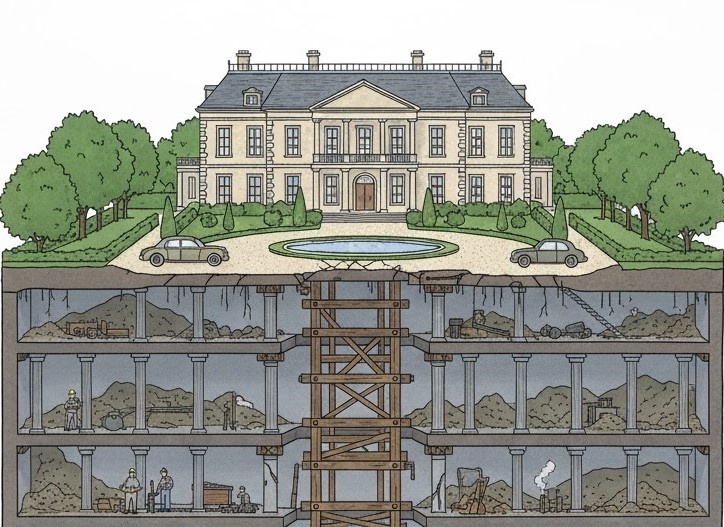

Linkage – let’s consider Ambatovy once more: they source their own fuel, operate their own power stations; opeate their own port – the lack of linkage between mining and the wider economy is similar to the UK’s predicament. Focusing the economy on the City of London, without being a catalyst for the remainder of the economy presents something we has dicussed before.

The single point of failure.

Remember the Heathrow substation? One fire, international consequnces.

When you build your economy, your system, your supply chain – on one pillar, it is as much of a vunerability as it is an asset.

So what is the answer? It feels like I stress the word diversification over and over again – maybe I overrely on it.

Building in redundacy and resilience is key, it is much the same story for the supply of critical minerals (or energy transition minerals)

But if you are worried about resource curse, here is a thought to take away:

Passive taxation is not enough. You need a seat at the table, and a vested interest – that means you need to ensure soverignty over your resources.

It feels like the top of the new Magalsay agenda should be to revisit the previous governments agreements – with soverignty in mind. Or, to leverage their resource for support in green electrification.

The energy tranisition is critical, and resource rich nations – many of whom are resource rich – must be respected, and partners in this global revolution.